Treatment-Resistant Depression and the Role of HPA Axis Dysregulation

Depression is commonly described as a disorder of mood, thoughts, or neurotransmitters. Yet for many individuals, especially those with treatment-resistant depression, the roots of the illness lie deeper than chemical imbalance. A growing body of research points toward a disrupted stress-regulation system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, as a central biological driver.

When depression persists despite multiple antidepressant trials, psychotherapy, and lifestyle interventions, it often reflects a more entrenched physiological dysfunction. In these cases, understanding HPA axis dysregulation offers a clearer explanation for why symptoms persist and why approaches such as neurostimulation therapy are gaining clinical relevance.

How do the normal HPA Axis Functions?

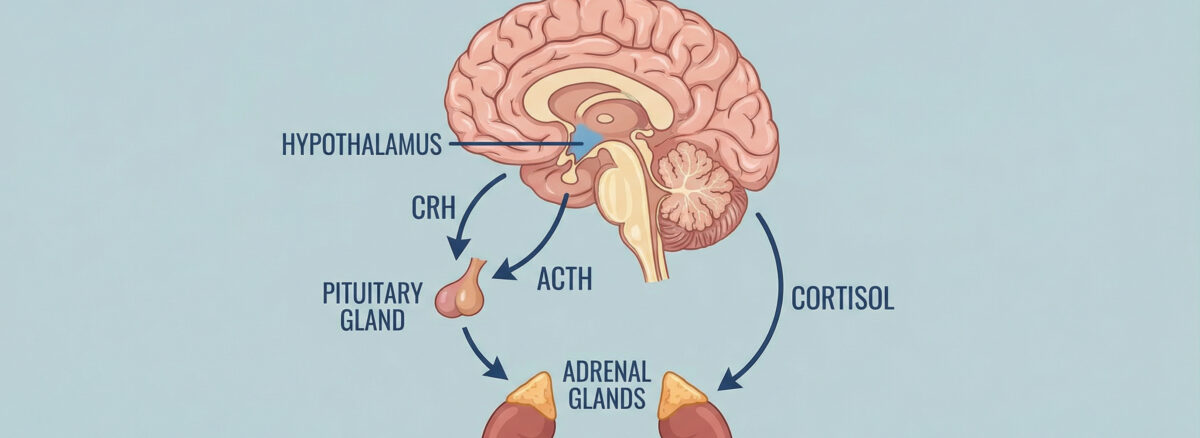

The HPA axis is the body’s primary stress-response system, linking the brain and endocrine system to help the organism adapt to threat. Under healthy conditions, this system is precise and time-limited.

Stress activates the hypothalamus, which releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then prompts the adrenal glands to release cortisol. Cortisol mobilizes energy, sharpens attention, and supports survival.

Crucially, cortisol also feeds back to the brain and signals the system to shut down once the stressor has passed. This negative feedback loop allows the HPA axis to remain flexible, activating when necessary and disengaging when safety returns.

Cortisol secretion follows a predictable daily rhythm, peaking shortly after waking and gradually declining toward night. This rhythm supports alertness during the day and restoration during sleep. In healthy individuals, the HPA axis is not overactive or suppressed; it is responsive, balanced, and self-regulating.

What Changes in HPA Axis Dysregulation?

In treatment resistant depression, this finely tuned system often loses its ability to regulate itself. Instead of short bursts of activation, the stress response becomes chronic, distorted, or blunted.

Some individuals experience persistently elevated cortisol levels, while others show a flattened response that fails to rise or fall appropriately. In many cases, the brain becomes less sensitive to cortisol’s feedback signal, meaning stress activation continues even when it is no longer needed.

This dysregulation keeps the nervous system in a state of constant alertness. Over time, excessive cortisol exposure disrupts hippocampal function, weakens prefrontal regulation, and amplifies limbic reactivity. These changes reinforce depressive symptoms and reduce the brain’s capacity to respond to treatment.

This helps explain why standard pharmacological approaches often fall short in treatment resistant depression. Medications may alter neurotransmitters, but they do not necessarily repair a stress system that has lost its off-switch.

Cortisol Curves in Chronic Depression

One of the most consistent biological findings in chronic and treatment resistant depression is an altered cortisol rhythm.

Instead of the healthy peak-and-decline pattern, patients may show:

- Elevated evening cortisol, contributing to insomnia and rumination

- Blunted morning response, leading to fatigue and emotional numbness

- Overall flattening of the curve, reflecting loss of circadian regulation

These abnormal cortisol curves are not just markers, they actively maintain depression by:

- Reducing neuroplasticity

- Suppressing dopamine signaling

- Impairing emotional learning

- Weakening stress resilience

Over time, this hormonal environment makes the brain less responsive to both medication and psychotherapy, reinforcing treatment resistant depression.

Trauma and HPA Axis Imprinting

Trauma plays a critical role in shaping long-term HPA axis behavior. Early life stress, chronic adversity, or repeated emotional trauma can imprint the stress system, locking it into maladaptive patterns.

Key trauma-related changes include:

- Sensitized CRH neurons

- Altered glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity

- Persistent threat signaling even in safe environments

This imprinting explains why some individuals develop treatment resistant depression despite adequate treatment. Their nervous system is not responding to present-day reality, it is reacting to stored physiological memory.

Importantly, trauma-related HPA dysregulation is often non-conscious. Patients may not report ongoing stress, yet their endocrine system remains in survival mode. This is where traditional talk therapy alone may reach its limits.

Why Conventional Treatments Often Fail

Most antidepressants are designed to modify neurotransmitter signaling. While effective for many patients, they do not directly address the endocrine drivers of depression.

In treatment resistant depression, the problem is often not a lack of serotonin or norepinephrine, but a misalignment between brain circuits and hormonal regulation. As long as the HPA axis remains dysregulated, depressive symptoms are likely to persist or recur.

This limitation has driven increased interest in treatments that can directly influence the neural networks responsible for stress regulation, including neurostimulation therapy.

How Neurostimulation Therapy May Reset Stress Feedback

Neurostimulation therapy, particularly transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), offers a distinct mechanism of action. Instead of acting chemically, it modulates the activity of specific brain regions involved in emotional and stress regulation.

TMS primarily targets the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, an area critical for top-down control over limbic and hypothalamic activity. By strengthening prefrontal regulation, neurostimulation therapy may reduce amygdala hyperactivity and normalize stress signaling to the HPA axis.

Emerging research suggests that this process can improve cortisol feedback sensitivity and gradually restore healthier diurnal rhythms. Rather than suppressing symptoms, neurostimulation therapy appears to help recalibrate the brain-stress interface itself.

This may explain why TMS demonstrates effectiveness in treatment resistant depression, even after multiple medication failures.

Neurostimulation Therapy

Neuroplasticity, Cortisol, and Recovery

Chronic cortisol exposure suppresses neuroplasticity by reducing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). This limits the brain’s ability to adapt, learn, and recover.

By reducing stress-driven overactivation and enhancing prefrontal control, neurostimulation therapy creates conditions that support neural repair. As plasticity improves, patients often experience better emotional regulation, reduced rumination, and increased resilience to stress.

Over time, these neural changes may allow the HPA axis to regain flexibility, supporting more durable recovery in treatment resistant depression.

Clinical Assessment and Monitoring

Evaluating HPA axis involvement requires moving beyond symptom checklists. A thorough assessment includes exploration of trauma history, sleep-wake patterns, stress sensitivity, and treatment response.

In selected cases, biological measures such as diurnal cortisol testing or dexamethasone suppression tests can provide additional insight. These tools help clinicians identify patients whose depression is driven by stress-system dysfunction rather than isolated neurotransmitter imbalance.

During neurostimulation therapy, progress should be monitored not only through mood scales, but also through changes in sleep quality, emotional reactivity, energy levels, and functional recovery. Improvement across these domains often reflects deeper biological recalibration.

Rethinking Treatment-Resistant Depression

Treatment resistant depression is not a failure of motivation or compliance. In many cases, it represents a stress system that has lost its ability to reset.

Viewing depression through the lens of HPA axis dysregulation allows for a more precise, compassionate, and biologically grounded approach to care. It also clarifies why neurostimulation therapy should not be seen as a last resort, but as a targeted intervention for a specific neuroendocrine dysfunction.

Recovery, in these cases, is not about pushing harder or trying more of the same. It is about restoring balance to a system that has been stuck in survival mode for far too long. At Mind Brain Institute, this neuroendocrine-informed approach guides how treatment-resistant depression is assessed, monitored, and treated using precision neurostimulation strategies.

Dr. Anuranjan Bist stands as a pioneering figure in the field of mental health, seamlessly blending traditional psychiatric methods with holistic wellness practices. With a profound understanding of the human mind and body, Dr. Bist has redefined therapeutic approaches by integrating Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) and Ketamine therapy with ancient yoga techniques, showcasing his innovative spirit and dedication to comprehensive care.